Article by Wayne Gillam / UW ECE News

UW ECE Professor Emerita Irene Peden helped to create pathways to success for women in engineering during a time when there was no clear or easy road. An exceptional researcher and educator with confidence, grit, and a can-do attitude, Peden broke down barriers and confronted institutionalized sexism during a time when career opportunities for women were very limited. Alongside her teaching and research, she was a leader in improving engineering education, and she was a passionate advocate for women in engineering throughout her life.

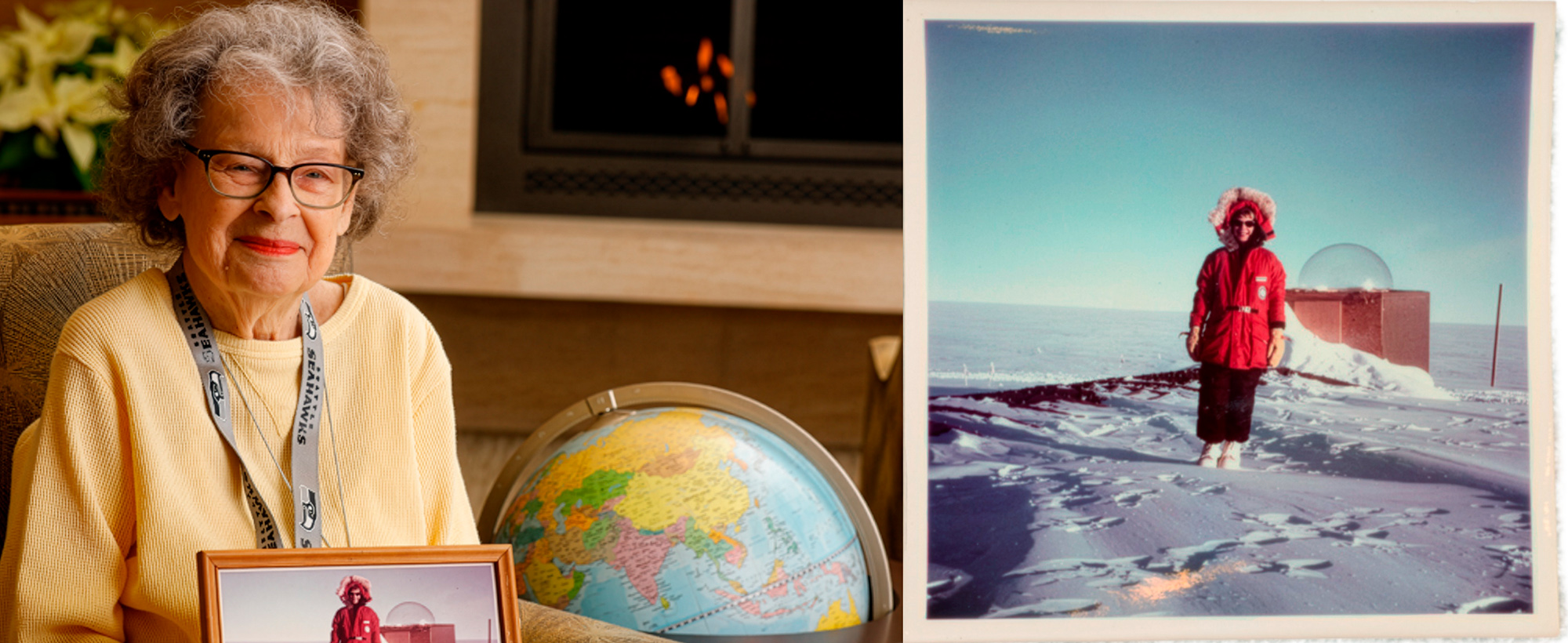

Peden passed away on August 22, 2025, just a few weeks before her 100th birthday. Her accomplishments, awards, and honors are too numerous to list them all here. But illustrated below are some key milestones from her life that reflect the contributions she made as a researcher, educator, and a pioneer for women in engineering.

A life well-lived

Irene Peden was born in 1925 in Topeka, Kansas. She was the oldest of three girls, growing up during a time when an engineering career was not considered by many people to be a good fit for a woman. Her mother, who taught mathematics and music, was a strong influence. According to Peden, it was her mother who instilled in her the confidence and strength necessary to overcome challenges and obstacles that were yet to come.

“I grew up knowing that if you want to do something, no matter what kind of roadblocks they throw in your way, you just do it.”

In high school, Peden discovered her love for science in a chemistry class. Because she was a girl, her high school teachers and counselors discouraged her from going into science as a career, but she was undaunted. After high school, she chose to attend Kansas City Junior College, where she studied chemistry and physics. She enjoyed both subjects, especially physics, but ultimately, she decided to pursue a four-year degree in electrical engineering, thinking it would provide a more viable career path. After two years at Kansas City Junior College, she transferred to the University of Colorado, where in 1947, she graduated with her bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering.

In high school, Peden discovered her love for science in a chemistry class. Because she was a girl, her high school teachers and counselors discouraged her from going into science as a career, but she was undaunted. After high school, she chose to attend Kansas City Junior College, where she studied chemistry and physics. She enjoyed both subjects, especially physics, but ultimately, she decided to pursue a four-year degree in electrical engineering, thinking it would provide a more viable career path. After two years at Kansas City Junior College, she transferred to the University of Colorado, where in 1947, she graduated with her bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering.

“As an undergraduate, I remember being particularly attracted to a course in transmission lines, which was related to electromagnetic propagation — the field I ended up doing research in. My research was in a totally different context, but I loved that course. Sometimes, things tend to coalesce.”

Peden spent the first decade of her career as a professional engineer. Her first job was as an electrical engineer at the Delaware Power and Light company in Wilmington, Delaware. In 1949, Peden and her husband moved to California, so he could attend Stanford University. There, Peden got a job as a research assistant in the Aircraft Engineering and Antenna Laboratory at the Stanford Research Institute (now SRI International). It was one of the few organizations in the area that would hire a woman in engineering. She made calculations and took laboratory measurements for antenna research. The experience whetted her appetite to learn more. So, through a company program offered at SRI, she enrolled in Stanford University to pursue a master’s degree in electrical engineering. Although she had become successful in her chosen field, Peden noted the challenges women in engineering faced in those days.

“I had a difficult time getting my first job. It was the hardest thing I ever did in my life, and I’ve done some very hard things. They would simply tell me, ‘We’ve never hired a woman before, and we’re not going to talk to you,’ and shut the door. I had a lot of that to deal with.”

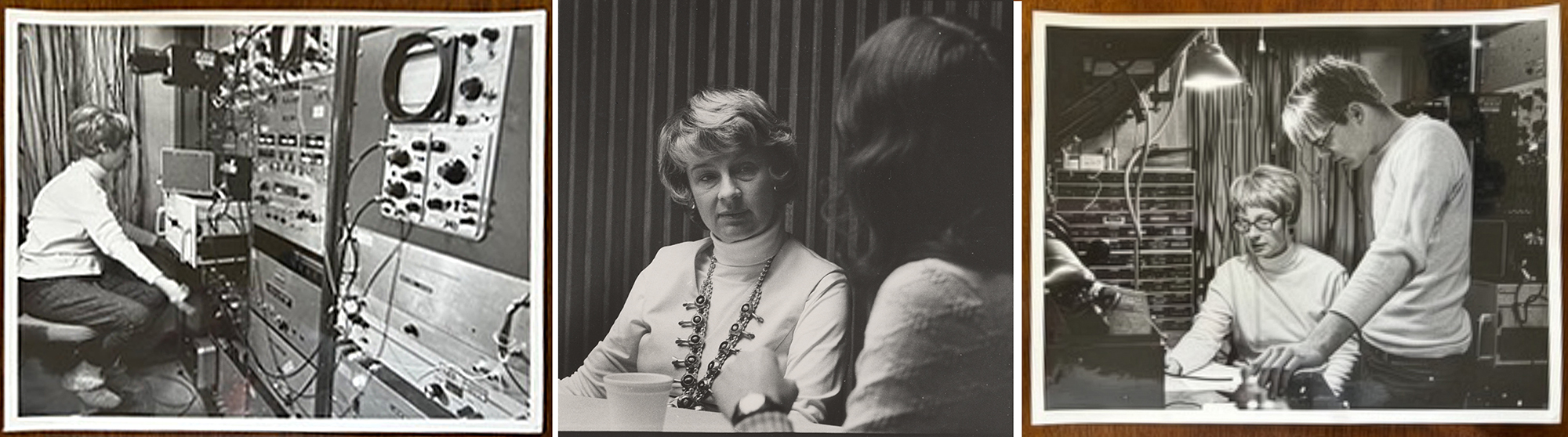

Peden was the first woman to receive her doctoral degree in electrical engineering from Stanford University. Initially starting her graduate studies part-time, she took a leave of absence in 1957 to go back to school full-time at Stanford. She later left SRI and got a job as a research assistant on campus to financially support her studies. The field had evolved by the time Peden returned to graduate school, so she had to work and study extra hours to catch up with her academic peers. Peden completed her master’s degree in 1958 and her doctoral degree in 1962. She conducted research for her doctoral dissertation in the Stanford Microwave Lab, focusing her work on measurement techniques for microwave periodic circuits.

“I have the first Ph.D. in electrical engineering that Stanford ever gave to a woman. And that was a long, lonely path. When I got my master’s degree in the electrical engineering department, there were two other women, but they didn’t go on. I was the only one who did.”

In 1962, Peden was the first female faculty member to be hired by the UW College of Engineering. After her graduate studies at Stanford, Peden accepted a position as an assistant professor at UW ECE (then UW EE). In 1971, she was promoted to full professor with tenure and remained in the Department until she retired in 1994 as a professor emerita. Her research interests covered several areas, including applied electromagnetics, radio science, antennas, and subsurface remote sensing. She spent close to 30 years at the University. Over her long career, Peden became one of the College’s most well-known and respected engineers. During her time at the UW, Peden served as associate dean in the College from 1973 to 1977 and associate chair in UW ECE from 1983 to 1986. She took a professional leave from 1991 to 1993 to serve as director of the Division of Electrical and Communications Systems at the National Science Foundation. She was known for her pioneering work and leadership in engineering education as well as her research on antennas, radio-wave propagation, and contributions to radio science in the polar regions. In 2018, she received the College’s Diamond Award for Distinguished Service in honor of her outstanding contributions over the years to students and the field of engineering.

“When I first came to Seattle, it was April. I got off the plane, and it was a perfect Seattle day. The sky was blue, there were puffy clouds, there was salt water, there was fresh water, there were mountains. It was so beautiful, it blew my mind. I spent the day with the Department, and I met many people who I really liked and were very welcoming. I ended up deciding that I wanted to come to Seattle and be at the University of Washington.”

The Professor Irene C. Peden Electrical Engineering Fellowship supports graduate students pursuing a degree in electrical engineering with a preference given to those students who demonstrate an interest and/or active role in advancing the research and career interests of women in electrical engineering.

“Knowing that I was the recipient of the Peden Fellowship motivated me to do better, work harder, and push my thinking a bit further every step of the way.” — UW ECE alumna Tamara Bonaci (Ph.D. ‘15)

Click here to make a donation.

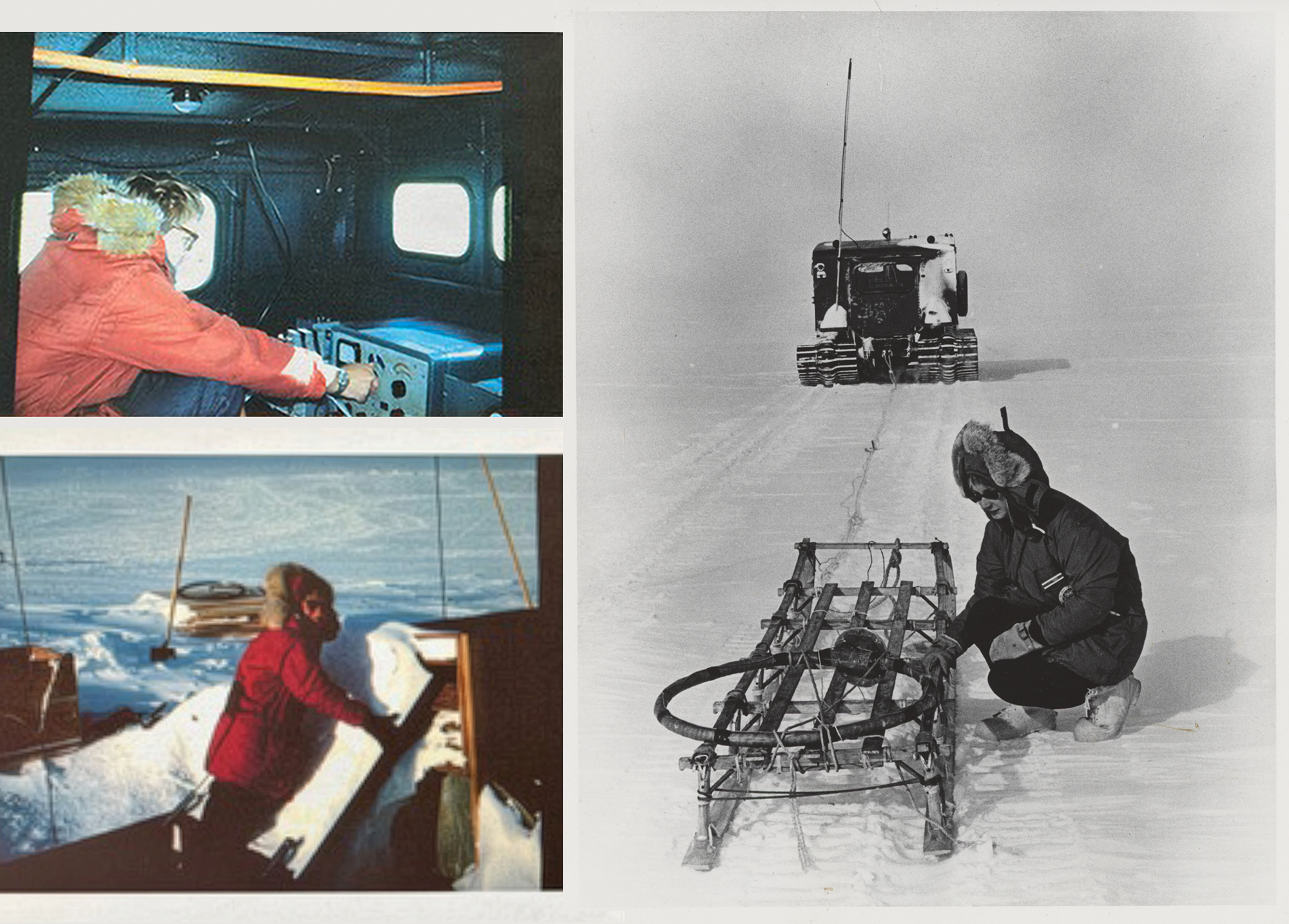

In 1970, Peden became the first American female engineer or scientist to conduct field research as a principal investigator in the interior of the Antarctic continent. She was told by officers in the U.S. Navy, who oversaw Antarctic research logistics at the time, that she could not go to Antarctica without another woman to accompany her. She was also unofficially told before she departed that if she did not complete her experiment and publish the results, another woman wouldn’t be allowed to follow in her footsteps for at least a generation. Peden’s research involved deploying a probe deep into an Antarctic ice sheet to study how very low frequency radio waves traveled through the ice and stone deep below the surface as well as how these waves bounced off the ionosphere, a layer of the earth’s atmosphere, high above. She and her students provided significant information about radio propagation and the polar ionosphere, buried antennas, electromagnetic properties of the ice sheet, and radio propagation over long paths in the polar regions. Her work was later expanded to measure the thickness of the ice sheets and search for structures underneath the surface using a variety of radio wave frequencies. In 1987, she received the U.S. Army’s Outstanding Civilian Service Medal for her research in the Antarctic. The Peden Cliffs in the Antarctic interior were also named in her honor.

“Antarctica is an exceedingly cold desert. It’s very, very dry, with low humidity. The first thing that happened to me was all my nails broke off. They did not regrow until I left. My glasses snapped in half. A technician used epoxy to put them together. I ended up with a big ball of epoxy right over the bridge of my nose, but it held the glasses together. That’s how I saw what I had to do down there.”

In 1989, Peden became the first female president of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, or IEEE, Antennas and Propagation Society. She was an IEEE Fellow and was the first woman to serve on the IEEE board of directors. Over the years, she held a number of positions in the IEEE, including Vice President of Educational Activities. Peden was quite active in other professional organizations as well. She was a member of the Society of Women Engineers, helped to form the collegiate section of the SWE at the UW, and served as its faculty adviser. She also participated in and was president of the Pacific Northwest Section of the SWE. She served on several national advisory committees, including the advisory committee to the Stanford University School of Engineering. She also served as board member and chair of several science and engineering associations, including the American Association for the Advancement of Science. She was active in ABET, chaired the organization’s Engineering Accreditation Commission and served on the ABET board of directors.

“I think working with your professional society is a good way to get known — going to meetings and giving papers and circulating and talking with people, so they know who you are, where you’re from, and what kind of work you’re doing.”

Peden received many prestigious awards and honors throughout her career, including in 1993, when she became the first of only five UW ECE faculty ever admitted into the National Academy of Engineering. That same year, she was named the National Science Foundation’s Federal Engineer of the Year and she was inducted into the American Society for Engineering Education’s Engineering Educators Hall of Fame. She was a Fellow of the AAAS, ASEE, ABET, and the SWE. She received the SWE Achievement Award in 1973. IEEE honored her with their Distinguished Achievement Award, the Centennial Medal, in 1984; the Haraden Pratt Award in 1988; and the Third Millennium Medal in 2000. She also received the Society’s “Man of the Year” award, which through its name alone, illustrated the sorts of obstacles she faced in her career.

“When I was admitted into the National Academy of Engineering, I was pretty elated. That’s one of the highest honors you can get in the field. My first thought was, ‘Gee, how did this even happen?’ I had a similar feeling the first night I spent in my little bunk twenty-five feet under the ice, 10,000 miles from home. ‘How did I get here?’ I felt very, very honored.”

In addition to her teaching and research, Peden was an outspoken advocate for women in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. She was known for helping others succeed by serving as a mentor and role model, and for working to expand pre-college engineering education for all. She fought for equal treatment for women, including through conducting salary surveys at the UW. Through her tireless efforts, Peden opened doors for female engineers to succeed on the UW campus. In 2006, the Professor Irene C. Peden Electrical Engineering Fellowship was created in her name. Today, UW ECE exceeds the national average of women in the field for undergraduate and graduate degrees awarded and the number of women in tenured and tenure-track faculty positions. This accomplishment is thanks in large part to Peden’s pioneering career and her work in education.

“My experience was that I wasn’t very discriminated against [in the UW College of Engineering] because I was the only one. You’re just a curiosity, a singularity in the field. However, when it becomes a small group, people get nervous. And then I think that’s where discrimination comes in. If you’re a member of a small group, you’re now a minority group, and there’s something about that. But after a certain point, if there are enough of you and if you also are good at what you do, then I think you can make a change. It takes some sacrifice, and you have to choose your priorities carefully, but it’s also very rewarding.”

Lead photo (upper left, top of page) by Brian DalBalcon, University of Colorado Boulder. All other photos were provided by UW Advancement and Jefri Donovan, Peden’s stepdaughter. Quotes above were lightly edited and sourced from:

- Transcript of March 2, 2002, interview with UW ECE Professor Emerita Irene Peden — by Lauren Kata for the Society of Women Engineers

- Transcript of May 8, 2002, interview with UW ECE Professor Emerita Irene Peden — by Brian Shoemaker for the Polar Oral History Program